I don’t care what anyone says, being good at ordering food isn’t easy. We all know someone who consistently fumbles in the face of pressure, caves in to that last-minute panic and changes their mind about what dish they want to eat at the final moment. Like bringing on three benched players to take a penalty shootout in a world cup final, that sort of panicked decision doesn’t usually end with promising results.

The person you want to be in charge of ordering when you’re at your favourite restaurant is someone with a cool head and a calm demeanour – the Tom Brady of choosing between the tagliatelle with wild mushrooms or the lamb ragù casarecce. The sort of person who can do the mental flavour mathematics of what everyone’s eating to make sure the meal is evenly balance. I’d like to consider myself an above average orderer but far from a star player like Mr. Bündchen. I’m more like the engine of the team; the player who rarely steals the headlines but, perhaps more importantly, never misses practice and never lets you down. I more than make up for my lack of natural ability (anyone who's dined with me will know that I'm regularly guilty of ordering a dud plate of fried something) with dogged enthusiasm. I’m a real menu nerd and find that they're often a great indication of what a restaurant is all about. Even if those menus are now, for the most part, completely digital.

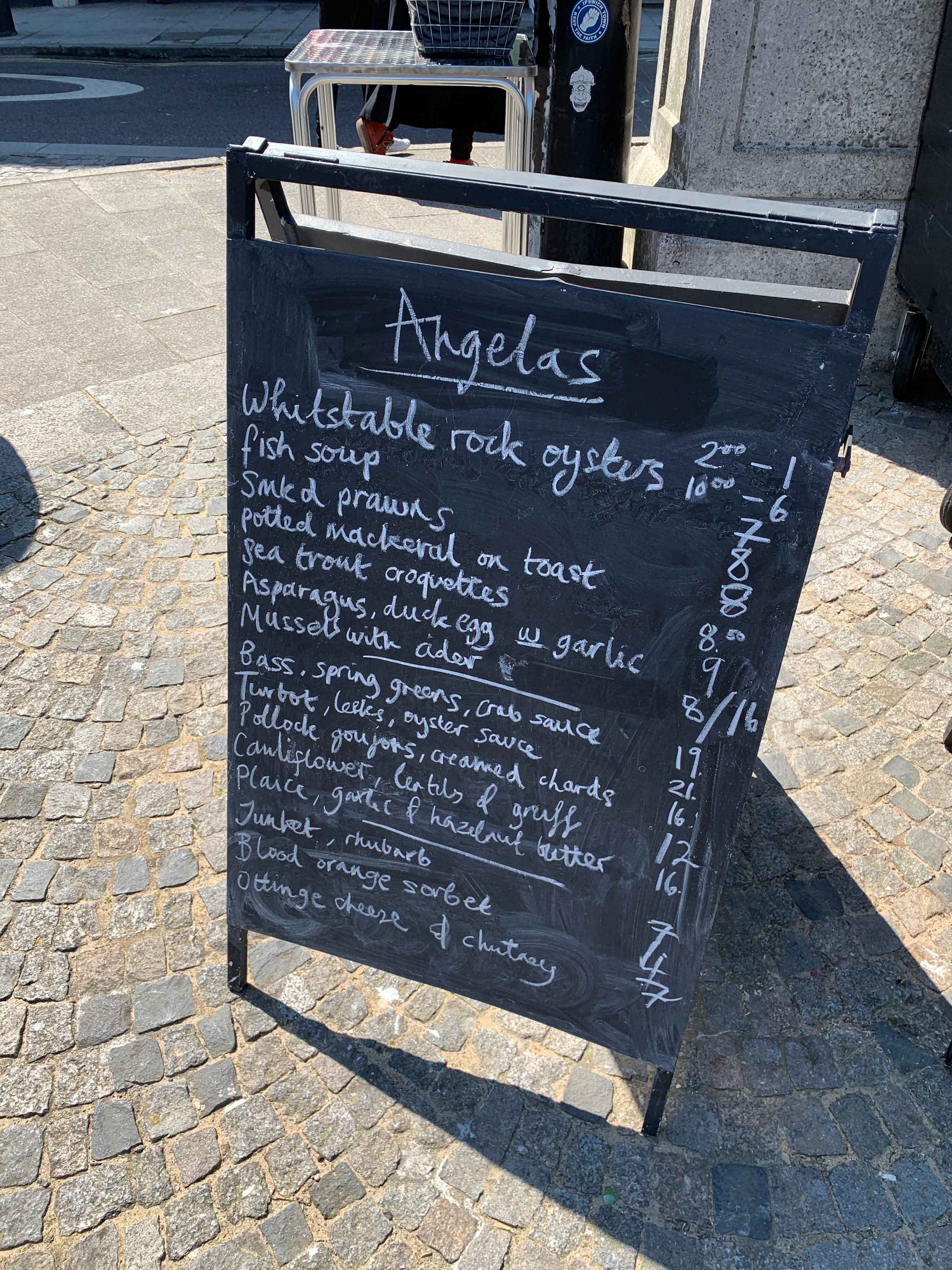

Ordering off QR codes in the peak of lockdown was convenient, if charmless, but I’m not surprised that they’ve stuck around in this sort-of-but-not-really-at-all-post-COVID world that we inhabit. The ability for a venue to change their menu at a moment’s notice once they’ve run out of specific ingredients is an obvious boon to both the back and front of house. It’s also cheaper than reprinting menus on a daily basis and saves having to disappoint each customer who has to completely alter their plan of attack after you tell them that you’re “actually all out of sole today, sorry”. Whether this is done via an app or a simple chalkboard you can write up and wipe down, however, is a decision that immediately sets the precedent for the rest of the evening.

Finding out a restaurant has run out of what you wanted and being forced to change your choice just as you were approaching the final hurdle, the server’s eyes boring daggers into you as you "um" and "ah" between two equally-delicious sounding plates, can be a lot of pressure. Even to an experienced orderer. It means re-thinking about the balance between your starters and the wine you’re ordering and altogether reconsidering whether you’re going to have enough room for dessert. Yes, it’s a first-world problem, but it’s one that I encounter far too frequently for my liking. Which is, in and of itself, a massively privileged thing to say.

When it comes to food, I’m also well aware that I think a lot more about what I’m going to eat than most other people.

In fact, a poll conducted by Gallup claims that most customers will spend an average of just 109 seconds reading a menu. That's roughly the length of a PinkPatheress song. While I’ll accept that might be the case at fast-casual sort of joints where you go in already knowing what you want to eat, I genuinely find it hard to believe that that’s the case at any restaurant higher up on the food chain. I know that if I’m going to be paying north of £15 for a plate of food, you best be damned sure that I’m going to take my time in making sure it's exactly what I want.

Making that decision, though, is no easy feat. Especially when the odds are stacked against you and the menu always seems to be actively working against you rather than with you. Primi, casse-croûte, short eats, snacks – every menu speaks in its very own language and it’s not always easy to decipher how large a portion you’re going to get will be or how many plates you really need. Desserts, for instance, are often separated from the main menu because of the fear that if customers see an enticing dessert before they start their meal, they’ll be less likely to order more starters or mains. It's simple menu psychology.

Everything is done for a reason and menu layout is an important factor to consider for any restaurateur. Science shows that our eyes naturally focus on the middle of a page, the top right-hand corner, and then the top left in that order. That trio makes up what is referred to by menu engineers as ‘The Golden Triangle’ – it is, therefore, the place that they’ll look to put the priciest dishes and the primest piece of real estate on a menu. The simple, sparse, and almost poetic lists you get placed on your table at trendy small plate spots obviously don’t adhere to this tactic but take a look at the menu of any chain restaurant and you’ll see it in action clear as day.

It’s not even uncommon for a restaurant to have a “decoy” item on the menu. The “decoy” is essentially a heinously expensive dish that’s used to make the prices of other dishes seem fair in comparison. The Golden Giant Striploin at Nusr-Et in Kensington is a prime example of that. Coated in two kilos of gold, that wagyu striploin comes in at a punchy £1,350; a price so steep that it makes the £315 sirloin or £40 tartare look like a bargain in comparison. Salt Bae might take it to the extreme but nearly every restaurant worth its salt uses a similar tactic in their pricing strategy. Some restaurants even refrain from including pound signs (“£”) or other currency symbols on their menus because studies have shown that diners spend more when restaurants don’t include dollar signs.

A more extreme version of that erasure of monetary consideration can be found in the literally price-less "Ladies’ menus" of the past where women were given menus that had no prices on them at all. A lawsuit soon put that practice to stop on the United States. Yet, even in the late 2000s, it wasn’t uncommon for women in the Middle East to receive price-less menus if they were eating at a table booked by a man.

The de rigueur method of restaurant service in the Western world (with starters, mains and desserts brought out in that logical sequence) is actually known as “à la russe” or “Russian-style” service – a method that was first introduced around the 19th century. Previous to that, “service à la française” or French-style service – which involved waiters presenting diners with all their food at once in a banquet-like fashion where you were expected to help yourself – was the norm. This all-at-once approach was visually impressive but technically flawed. Food got cold quite quickly and the free-for-all to get the choicest bits first meant that not everybody at the table could taste what they wanted or how it was intended to be eaten.

It’s easy to see why the Russian style became the dominant mode of service. However, I’d be lying if I said I couldn’t see a restaurant in Stoke Newington or Ancoats trying to bring back that service à la française and banging out endless tureens as some sort of “unique dining experience” gimmick.

The French, after all, have always had a firm grip on culinary trends. The word “menu” itself is (surprise, surprise) French, derived from the Latin “minutus” which means something that’s been reduced in size or made small. It's an apt word considering how a menu is, at its most rudimentary reading, a restaurant made small – a statement of intent and a culinary manifesto distilled onto a single piece of paper.

The truth is that less is often more when it comes to menus. Having plenty of options at your disposal might seem like a great idea (appealing to a larger audience, and all that) but having too much choice can be detrimental due to a phenomenon known as ‘choice overload’. I also like to refer to it as the “Frankie & Benny’s Brainfart”. ‘Choice overload’ is essentially when your brain becomes so burdened with the number of choices and decisions to make that, as a result, you actually become more likely to order less.

With that in mind, having a smaller and more concise menu seems like the best approach for a restaurateur that wants to tempt people into ordering as much as possible. The option to order the whole menu (plus four soft serve ice creams) at Forza Wine in Peckham, for example, is an absolute bargain if you’re dining with a group of mates and a great example of how smaller menus can be more profitable. Not only that, but that Harry Potter “we’ll take the lot” procedure also gives diners a more pleasurable experience; it removes any arguments over what to order and gives you a more holistic view of what the place does best.

Small menus are also better for the environment. Having a very select number of dishes means chefs only need to order a certain amount of food to make their dishes, reducing the potential food waste created by offering an endless array of options that not enough people actually want to eat. While choice seems appealing, it’s easy to end up like a deer caught in the headlights. I’ve had this on numerous occasions when approaching restaurant wine lists as, at a certain point, I just give up and go for the second or third-cheapest bottle available. That’s choice overload in action yet again. But then what’s the perfect amount of choice to give someone? Is there a magic number of dishes that's just right?

Well, a study conducted by Bournemouth University found that restaurant customers do actually have an ideal number of menu choices. And that number is apparently “about 6 for quick service and varying between 7 for starters and desserts to 10 for main courses in fine dining restaurants.”

I don’t know about you but the less choice I’m given, the more I tend to enjoy a meal. That’s why my world-changing, positively revolutionary advice is this: speak to the staff at the restaurant and ask them for their recommendations. They know the food better than anyone else and it's the best way to ensure you have a good meal when you’re eating out. A good waiter should. be able to swerve you away from ordering those appetising-sounding but bland-tasting croquettes. Plus, even if the food is bad after all those personal recommendations, at least you can go home blaming someone else rather than wallowing in your own poor ordering. Everybody goes home a winner.